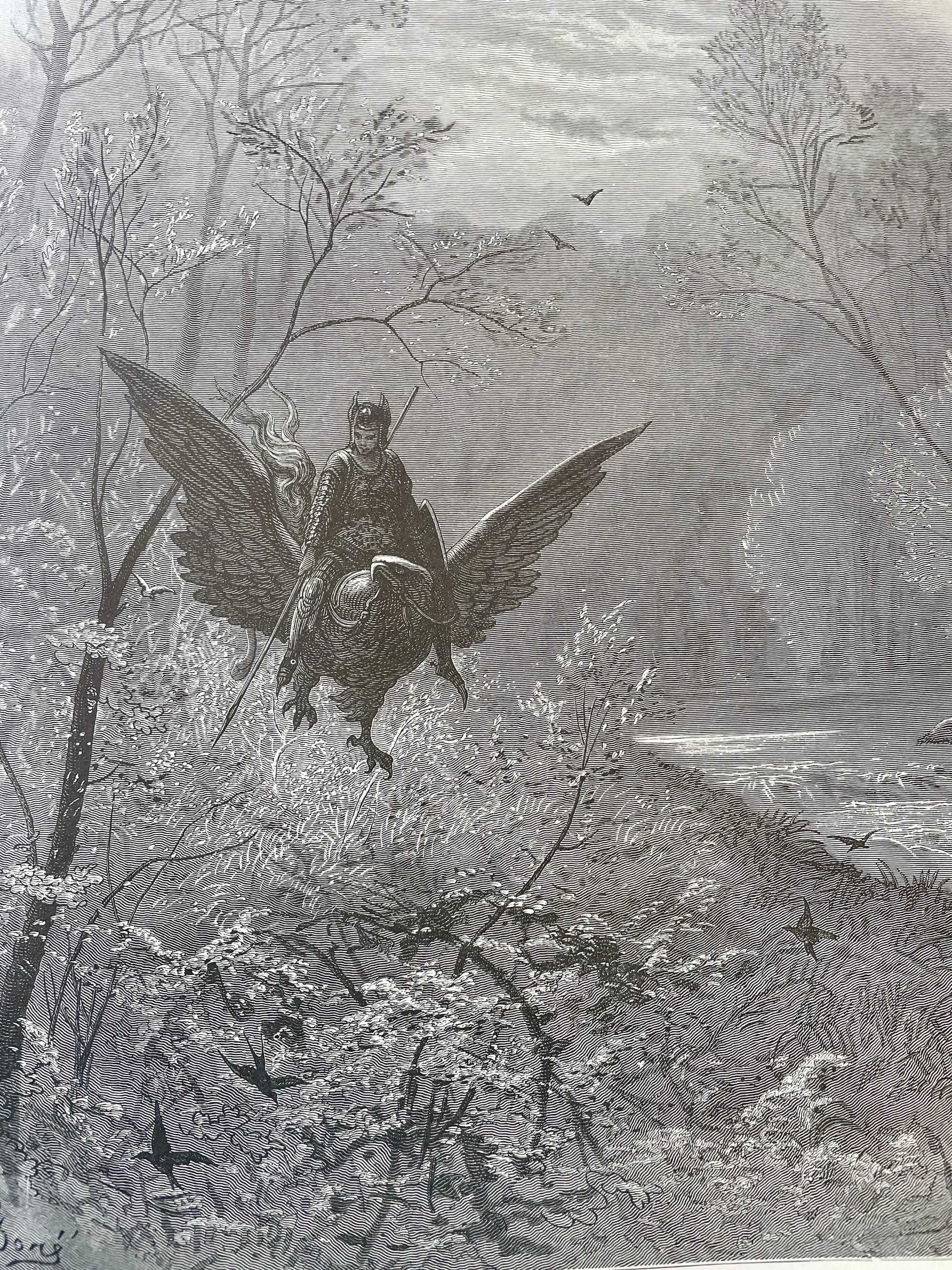

Atalante’s Castle

Reflections on interpretation

To intellectualize a work of art is to debase its beauty by reducing it to an interpretation. During an age where the intellect is neglected, attacked, distrusted, or censored, the intellect as Susan Sontag writes, takes its revenge on art by attempting to simplify it into an idea, say Freudian interpretations of literature. In her monumental essay Against Interpretation, Sontag advocates for “an erotics of art,” where instead of interpreting a work of art, a critic simply describes its style. Only then art retains its mystery and wonder, and the observer leaves the aesthetic experience with a world enriched, not impoverished. Oscar Wilde writes something similar in the preface to The Picture of Dorian Gray, where he defines the critic simply as someone who writes their impression of beautiful things.

It comes as no surprise then that the best critics are the great artists themselves. In literature I can think of no better critics than the likes of Borges, Vargas Llosa, Nabokov, Woolf, Paz, Calvino, Rushdie, Poe (the latter writes of how only great artists know what it takes to produce great art, hence they are the only ones in a position to speak of it). Their criticism, unlike a great deal of the old established critics like Edmund Wilson or Harold Bloom, is as timeless as their poetry and fiction, and at times, given their love for the subject matter, offers their richest prose.

A vivid example of this is how H.P. Lovecraft describes the work of Lord Dunsany in his famous essay Supernatural Horror in Literature: “Beauty rather than terror is the keynote of Dunsany’s work. He loves the vivid green of jade and of copper domes, and the delicate flush of sunset on the ivory minarets of impossible dream-cities. […] His prismatic cities and unheard of rites are touched with a sureness which only mastery can engender, and we thrill with a sense of actual participation in his secret mysteries. To the truly imaginative he is a talisman and a key unlocking rich storehouses of dream and fragmentary memory; so that we may think of him not only as a poet, but as one who makes each reader a poet as well.”

Those words could only be written by someone who not only traveled Dunsany’s works through reading, but also forged such artificial dreams himself. Encountering Dunsany both in literature and in person changed Lovecraft’s life. Fantasy became inseparable from his identity, and now stands as his imperishable mausoleum.

While we may not intellectualize art, does art in turn do the opposite to reality? Does it make reality intelligble to us? [1] The wider world by any accounts is a truly bizarre and unknowable place of both infinite horror and endless beauty. Our attempts to rationalize the world fail to grasp it entirely. Science and critical thought offer only the tools to conceptualize and navigate our surroundings. It is one thing to quantify and conceptualize climate change, another to truly come to terms with the epochal significance of an anthropogenic, geological process. Clearly we are struggling to do so. The understanding of a hyperobject like climate change comes not only as a collective endeavor, an international effort between scientists, but also as a social, political, and historical process, something witnessed through a span of time far longer than an individual’s life, maybe even our civilization’s. Climate science is notorious for perversely shattering almost by the day what yesterday we feared was true.

The intellect is not omnipotent, and the world cannot be digested only through an ideological framework, or by the single use of logic and empirical reasoning. This is why Nietzsche’s thought speaks so acutely to us. He is so stimulating because he only hints, suggests, invites the reader to creatively construct themselves within his words. It is telling that Nietzsche’s first book and the departure point of his philosophy is The Birth of Tragedy, a work that explores the origins of Greek drama in the Dionysian festivals. His interest is not entirely for the sake of tragedy itself. Nietzsche sought to understand the kind of consciousness that gave rise to the plays, a consciousness that was brave enough to gaze into life unflinchingly, with extreme sincerity, and respond to this rawness not with logical explanations, not even with political solutions, but by inventing drama. Nietzsche’s philosophy amounts to an affirmation of life. His subject is life itself, or the conduct of life—in other words, ethics. And for this he found it necessary to start his inquiry with art rather than Socratic philosophy.[2]

Why? Because art does not need to determine anything. On the contrary, moralistic art is the most dated (this is Edgar Allan Poe’s greatest aesthetic legacy to literature, to free it from a lecturing pedestal, thereby unleashing the modern short story and heralding the later coming of the Vanguards). Art dares approach the meaninglessness of the world, and not only tames its horror through the psychological release of catharsis in the plays of Sophocles, not only lets us glimpse its wild beauty in the odes of John Keats—the tragedies themselves are Horror, and Keats’ odes Beauty. They are as much a part of the world as sunrises, slaughterhouses, snow-capped mountains, battlefields, wind-whipped seas, decaying cities, flowers blossoming in the sun. More than negating the will through contemplation, art feeds the will by itself becoming an object of desire.

Not satisfied with quantifying phenomena, or actively participate in the moral judgment of phenomena, we may choose something higher: awe. Quantifying something as sublime as a black hole does not necessarily lead to its understanding. For this we need an emotional response, which can only be horror as expressed through art. This was the approach of Rennaissance masters like Da Vinci, whose sketches are inseparable to his scientific thought, or Romantic poets like Goethe. Art cannot be intellectualized, but given we inhabit only a human representation of reality, built by our cultural and individual experience, life in turn may be intellectualized in art, and this only ever as a starting point, a window.

And while intellectualizing art impoverishes its aesthetic experience, intellectualizing reality through art enriches our experience of the world. The world we forge through our hearts, memory, and imagination is more beautiful, more interesting, and more full of wonder because of art.

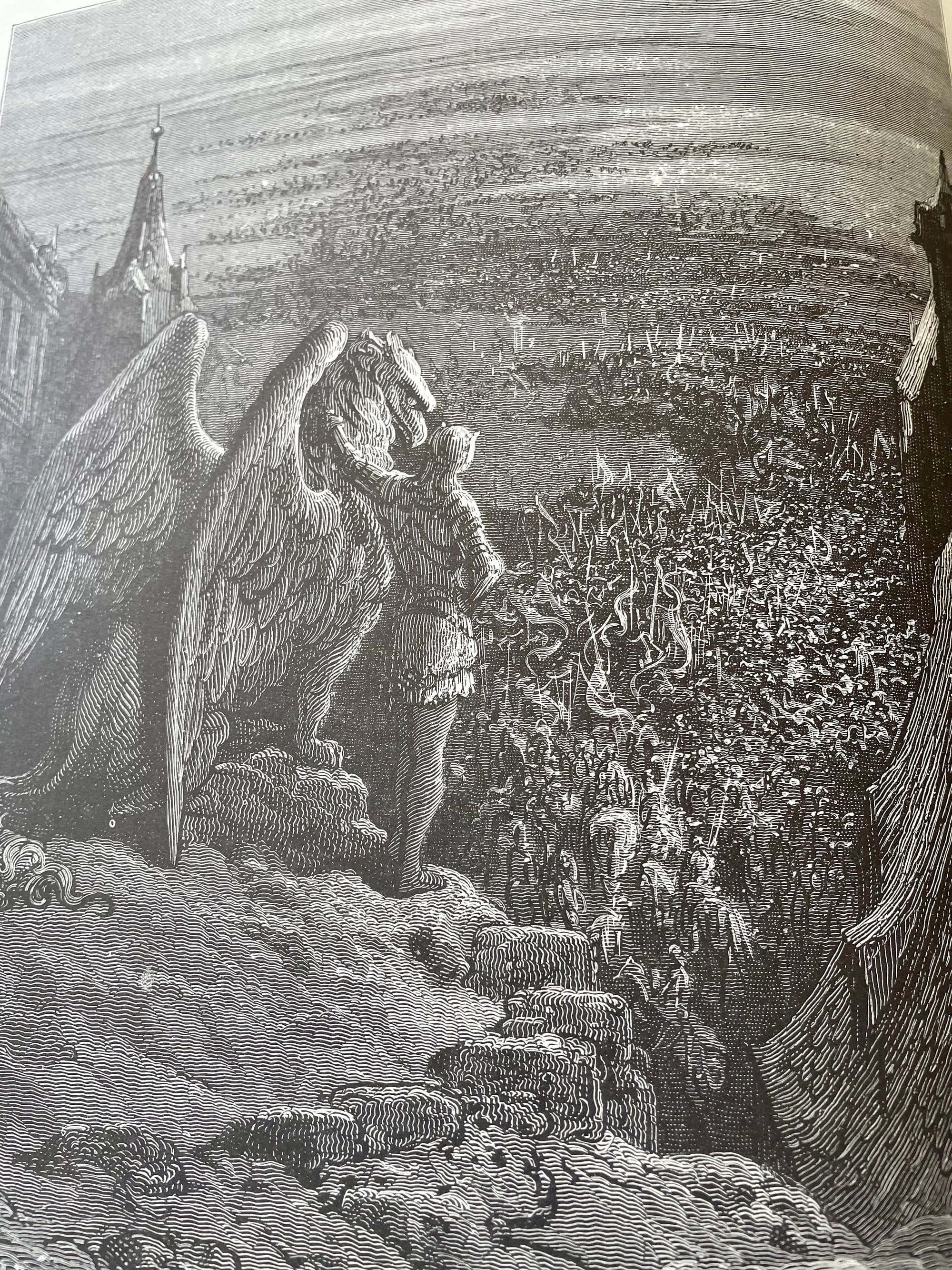

For instance I often think of a scene in Ludovico Ariosto’s epic Orlando Furioso, written in the sixteenth century, entirely in relation to our times. In that moment in the story the knight Ruggiero chases a giant who’s kidnapped his beloved Bradamante. But the giant turns out to be an illusion cast by the sorcerer Atalante, who leads Ruggiero into a castle that is itself an infinite mirage, where for eternity knights are doomed to chase down their enemies, or shadows of their enemies. Our modern castle is our screens, those glass prisons for the will, where we chase representations but not the objects themselves. In them we are lost chasing shadows we never reach.

The screen is an astonishing instrument of power and propaganda that mimics reality, but offers only representations. Objects in themselves are perhaps unknowable, but greater representations lie in greater castles. In the poem Bradamante herself is the one who breaks the illusion and rescues Ruggiero from the sorcerer. Curiously, Atalante wanted to keep Ruggiero within the castle not out of malice, but as a means of protecting him from the world. The castle was a shelter. What follows its shattering is the continuation of the wildest, most extraordinary adventure sprawling across the world and beyond, a poem whose fantasy and beauty has ceaselessly dazzled humanity, from inspiring the likes of Shakespeare and Cervantes, to nowadays being regarded as a grand precursor to the genre of science fiction—poetry that can only be likened to a relentless symphony of wonder.

Not all art. Much of contemporary art has completely sublimated into a world of its own. A toothbrush in a gallery, a vacuum cleaner that is more of a breathing creature behind glass—contemporary art, heir to the Vanguards, has entirely conceptualized itself, has made a dialogue in and of itself, and admirably recognizes itself as the only existing world (within the context of a gallery, we don’t approach a toothbrush, but a new object that is closer to an idea; note that I don’t think this makes it any less valuable artistically, only less of interest for this post). Increasingly this type of art uses politics as a bridge to return to our world.

As a digression, I find it interesting that the greatest legacy of the vanguards was a total freedom of expression, a window to the wildest stylistic choices. Yet contemporary literature has chosen to relinquish and shelter itself from this hard-fought freedom. The prose the establishment admires most is the Hemingway kind: short, clean declarative sentences that mimic the Bible or the newspapers. ↩︎Nietzsche would call that consciousness Dionysian (or sometimes even the anti-Christ for depositing its faith in this life instead of an afterlife) not for historical purposes. His interest was not so much the past but the future: to provide an ethical framework for the superman. ↩︎

Gustave Doré found his way into this newsletter before. He was so astute that before he died he hurried to illustrate as many great works of literature as he could, ensuring the immortality of his name and the growing value of his work through the ages. Western culture glorifies change above all, exults the future in many ways. I think of him to remind myself that the best things are often the ancient things. Here are a few more of his wonderful illustrations of Ariosto’s poem, work that is “a key unlocking rich storehouses of dream and fragmentary memory.”