Fade to Black

Heavy metal as a force of civilization.

Where to even begin with heavy metal? Let me begin with those who played a major role in its invention and reinvention, probably my favorite band of all time, and my daily writing music. They who have become an espresso of inspiration every morning for me: bitter, electrifying, and awakening.

Metallica is a musical juggernaut. Their albums are wide-ranging variations on the theme of playing fast and loud: from the electric Ride the Lightning, full of ghastly songs like the Hemingway-inspired For Whom The Bell Tolls to the vengeful, fan-favorite Creeping Death–to The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly inspired art of Master of Puppets (thereafter opening their concerts with Ennio Morricone’s The Ecstasy of Gold), detonating the searing war indictment Disposable Heroes, as well as the title song, a horrifying meditation on drug addiction, before reaching the jewel and crown of it all: Battery, their strangest and most terrifying song, a song about that terrible voice that nests within the throats of all artists, the source of all our joy and inspiration, yet at times it also represents something scary, something dangerous and demanding great sacrifice, something that speaks from within us whether we like it or not–all this inevitably twisting into Metallica’s most politically charged and defiant album ... And Justice For All, opening with none other than Blackened, their heaviest song by far, a song about the fears of nuclear Armageddon, this subliming to their most well-known and perhaps most intimate work, The Black Album, where shine tracks like Nothing Else Matters, Sad But True, The Unforgiven, and of course Enter Sandman, and after its immense commercial success the band did not sit idly, their unquenchable thirst for reinvention gave us with the heavy rock of Load and Reload, my personal favorite of all the sounds and styles they achieved, culminated in the frantic thrash of St. Anger; inevitably Metallica dissipates with the transitional album Death Magnetic (which nonetheless is not without its memorable moments) until the band roared back into full force with the merciless Hardwired ... To Self Destruct and their most recent work, 72 Seasons, an album that embodies the basic principle that anyone who wishes to create art and use art as a way to speak to others must first gaze into the darkest and most terrible corners of themselves, this exemplified by the exuding inward gaze of Too Far Gone?, Room Full of Mirrors, and Screaming Suicide.

Metallica’s albums are all distinct and innovative in their own ways. Their best, however, is the one most charged with youth and freedom, that which would serve as the foundation for their greatest work.

Kill ’Em All changed the history of rock and roll. It opens with Hit the Lights, a song silent at first, and then like Wagner’s operas where he conceived the orchestra playing from what he called "the abyss," a section lower than the stage–so does Metallica in their very first song, little by little, the sound of metal rises from the depths before engulfing you entirely. It is only an announcement, for it is followed by The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse with its galloping chords and apocalyptic metal, the four horsemen of course being the four members of the band. Like the first work of the greats, such as Patti Smith’s Horses, Kill ’Em All represents a manifesto and an oath. It embodies the artistic values the band will pledge their lives to, the sound of living fast as the glorious Motorbreath roars.

The most admirable song in my mind from the album is Anesthesia (Pulling Teeth) which is Cliff Burton’s three minute bass solo. The bass here sounds horrible and distorted, yet Burton’s genius is the fact he tries to make it sound beautiful, beginning by playing harmonious scales reminiscent of classical music. The result is something like a horrid monster attempting to play the part of a civilized person. Soon after the bass gives up producing the sounds of pretty harmony, and degenerates into a delirium of fire and freedom, celebrated when Ulrich’s drums kick in, and the bass delights in its twisted nature and wretched sounds, reaching its climax in the opening chords of one of Metallica’s greatest songs: Whiplash, a celebration of metal culture, of the collective derangement that is a metal concert. I’ll never forget standing in the thick of the crowd in Mexico City, as the first chords of Whiplash erupted, everyone around me jumping to the hymns of the derangement launching at us with the force of a freight train, and in the cauldron of the arena, for a few moments I stood completely still, engulfed by the communal fire, before disappearing like a shadow in the path of this luminous, summoned sun that burned for two hours straight into the night.

As a writer I ask myself, is literature capable of this, of transmitting this flame of a feeling that is like a star bursting with fires eons old and falling forever in an abyss without bottom, beginning, or end? Can literature transmit the great power and delirium that comes from staring at the numinous evil hidden behind the veils of an illusory real?

It does so routinely. Horror fiction, and Weird fiction in particular, is heavy metal’s literary counterpart. No wonder there is plenty of overlap between the two genres; in fact one might say heavy metal is among the most literary contemporary musical genres. From Mastodon’s songs about Moby-Dick to Iron Maiden’s The Rime of the Ancient Mariner to Metallica’s The Call of Ktulu (among so many other metal adaptations of H.P. Lovecraft’s work), heavy metal in fact borrows its fire from the Weird, Weird being the human mind’s approximation to unfathomable evil and the sublime, be it embodied in Lovecraft’s chimeras or the phantom whiteness of Melville’s whale.

Weird itself evolved from a rich tradition of Nightmare transcribed and recorded throughout history, ranging from Dante’s descriptions of hell to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. This is the genre that is a mere window to the bottomless depths of human fear, shaping horror into a disquieting yet all-too alluring beauty.

Weird at its best represented modernism and was a part of the great artistic vanguards of the twentieth century. It signified a new way of conceiving art, a philosophical manifesto that did not shrink from the naked horrors of history, the barbarity that erupted from technological innovations applied to murder on a scale impossible to comprehend. As such one finds strains of Weird in the work of the twentieth century’s greatest writers: from James Joyce’s hellfire descriptions in Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man to Jorge Luis Borges to William Burroughs. No surprise currently that contemporary writers of the caliber of China Miéville, Samantha Schweblin, Mariana Enriquez, among so many others build their unique houses of nightmare on these foundations.

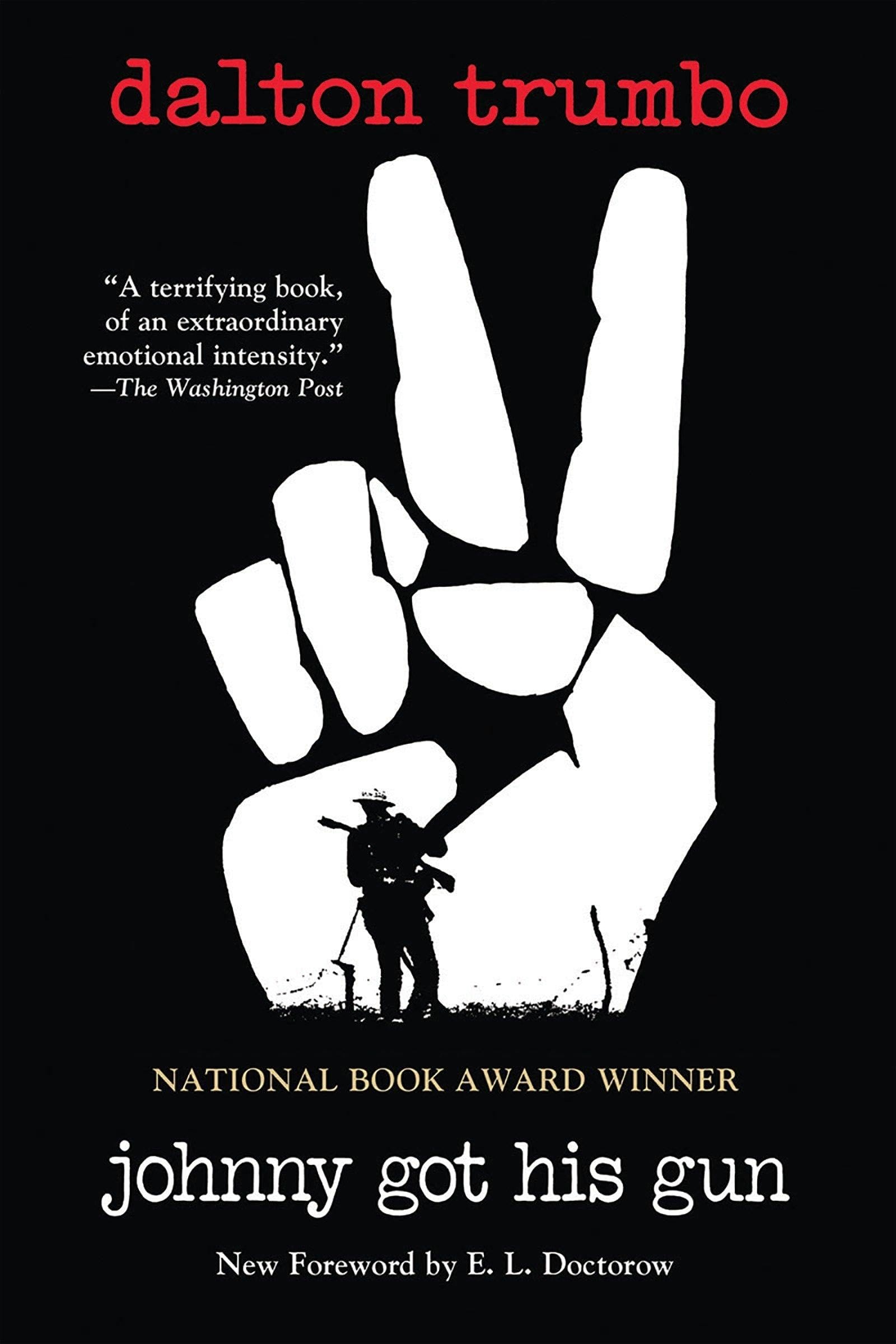

Metallica has many great songs but really two masterpieces: One and Fade To Black. The former is a song adapted from one of the most harrowing books you can ever read: Dalton Trumbo’s Johnny Got His Gun. The novel is about a mangled soldier who lost his limbs, face, eyes, and tongue during war. It takes the form of the stream of consciousness of this man who cannot move, who cannot live and cannot die, who endures a hell in a hospital bed, visited only by the people who sent him to the front.

One tells this horrifying, truly anti-war story. Like the band’s best songs, it is sad and simple at first, with few notes and chords inside a deep and terrible silence plagued only by the locust sounds of machine guns, helicopter blades, and distant screams. As the song goes on and the fallen soldier wishes for death, the physical and psychological flames of One grow higher and louder.

Let’s not fall completely into idolatry. Something as successful as Metallica is destined to become a brand, unless it is deliberately imploded by its founders (what Roger Waters attempted to do in many ways when he left Pink Floyd). Metallica’s failings are well-known. I’d argue worse than the Napster fiasco–which I think is normal considering streaming was an emerging technology back then and musicians were rightfully worried about their copyright, a concern now glaringly evident by the way LLMs and Big Tech platforms routinely trample intellectual property laws with absolute impunity–is for instance the Freeze ’Em All Concert, when they played in Antarctica under the auspices of Coca-Cola.

For all of Lars Ulrich’s talk that Metallica does not meddle into politics, One is and can only be a political song, deeply uncomfortable to a country whose economic growth depends on the military industrial complex, on the basic premise that if there is war, there is money. The band has at times cheapened One when they play it live, relegating its imagery to the First World War, when it could not be more relevant and contemporary.

Even so One retains its extraordinary power, searing all the so-called courageous and nationalist talk surrounding war, exposing it as nothing more than a destructive evil, the lowest humanity can ever sink, an agony that lingers for far longer after its bellicose flames are quenched.

Often the establishment derides pacifists as naive hippies who don’t know anything about how the world actually works, about real politik. To the old men who exult war from the safety of their government palaces, the Modis acting like brave lions crying orders from the rear, the manly Putins sending young Russians to the front, the Bidens who urged Ukraine to lower the conscription age, the Trumps who organize military parades for their birthdays as spectacular displays of vanity, the Netanyahus who find in Gaza’s children a dire threat to the national security of a nuclear-armed superpower, the "military experts" who decry war as a "viable means of solving issues between countries"–to these old men and their arms dealers you wish you could play these lyrics at full volume and on repeat in their minds and the hollowness of their plastic hearts:

Landmine

has taken my sight

taken my speech

taken my hearing

taken my arms

taken my legs

taken my soul

left me with life in Hell.

Recently I had the privilege of listening to Cornel West deliver a lecture in person. He said that during all his years studying and teaching in academia, never once did anyone discuss the phenomenon of war in human history. Isn’t that something? War is the unspeakable, a great and terrible taboo, particularly if one is part of a system where it represents such a lucrative endeavor.

Metallica’s other masterpiece, Fade to Black, also explodes another unspeakable silence permeating our disquieting civilization: suicide. It is an abominably sad song, culminating in one of the best guitar solos in the history of rock, a solo that is an outro as well, and as it represents the final goodbye, it reminds me so much of Dylan Thomas’ poem Do not go gentle into that good night. Rage, the song tacitly roars, rage against the dying of the light.

Cornel West asked during the lecture, when we listen to music, and it brings tears to our eyes, where do those tears come from? The question to me is not where but what are those tears I never fail to shed when I listen to the final solo of Fade to Black–tears that are not water but flame, erupting from the burning coals of my eyes?

What is the name of this mixture of sadness and wrath, this burning sorrow, to borrow from Natalie Diaz, these ever-blooming wounds?

The name is this world of will and representation, the relentless grip of our historical circumstance, the rancid system we are forced to live in, the sinister nature of Power, so pathetic in its banality, that makes us believe our dignity is not innate but dependent on its values. Nausea in Sartre’s sense is a symptom of a greater condition, a shared and collective madness disguised as a range of ideologies.

Borges remarks that in order to write a single book one requires the creation of the whole world and the whole of history. The same is true for these glorious songs that stare at great truths as unflinching as eagles flying straight into the sun. They are forces of civilization, allowing the discharge of our horrible nausea that inevitably bottles in the machinery of modern times, rinsing us in a collective, ritualistic experience, and make us relish life in its totality.

Like tragedy before it, heavy metal redeems life in the eyes of the intellect by allowing it to break free from the fetters of rationality, its more Apollonian character. It invites us to remove the "pale cast of thought" as Shakespeare calls it in Hamlet, and lay bare our wounds.

Through heavy metal we share this terrible burden, the great anvil we feel on our chests that can make us feel so lonely at times, with millions others who have also experienced such darkness. Its thunder helps perpetuate a civilization that deludes itself of its civility. By all this I mean that heavy metal is far beyond the therapeutic connotations of catharsis.

It is Family.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Metallica played for an estimated one and a half million people in Moscow. They were the first rock band to play in Russia. The response was rather enthusiastic.